Part Two: Inappropriate Speed

In the second of our new three-part series, we look at one of the three biggest causes of truck crashes – inappropriate speed – and offer expert advice on how to reduce the risks of a speed-related incident.

A combination of tighter regulation and advances in truck technology has seen the proportion of major truck crashes caused by inappropriate speed decline dramatically over the past two decades.

Back in 2003 inappropriate speed was the dominant cause of 26.1 per cent of major incidents – rising to a high of 31.8 per cent in 2009, according to the NTARC Major Accident Report produced by National Transport Insurance (NTI). This dropped to a record low of 12.5 per cent in 2021.

NTI Transport and Risk Engineer Adam Gibson attributes this stark advance to two major factors: the roll-out of Chain of Responsibility (COR) laws from 2014, which placed a legal obligation on all parties to take all reasonable steps to ensure drivers do not commit a speeding offence; and the increased use of heavy vehicle stability safety technologies.

Despite this improvement, inappropriate speed still ranks as a leading cause of truck occupant fatalities, accounting for 20 per cent of the total in 2020.

Inappropriate Speed Does Not Equal Speeding

Gibson stresses that exceeding the signed speed limit isn’t the problem. The overwhelming majority of NTI’s recorded speed-related crashes don’t involve breaking the legal threshold, he says.

Inappropriate speed, Gibson explains, is when a truck is driven too fast for the road geometry, weather conditions, vehicle loading, road surface or any combination of these factors.

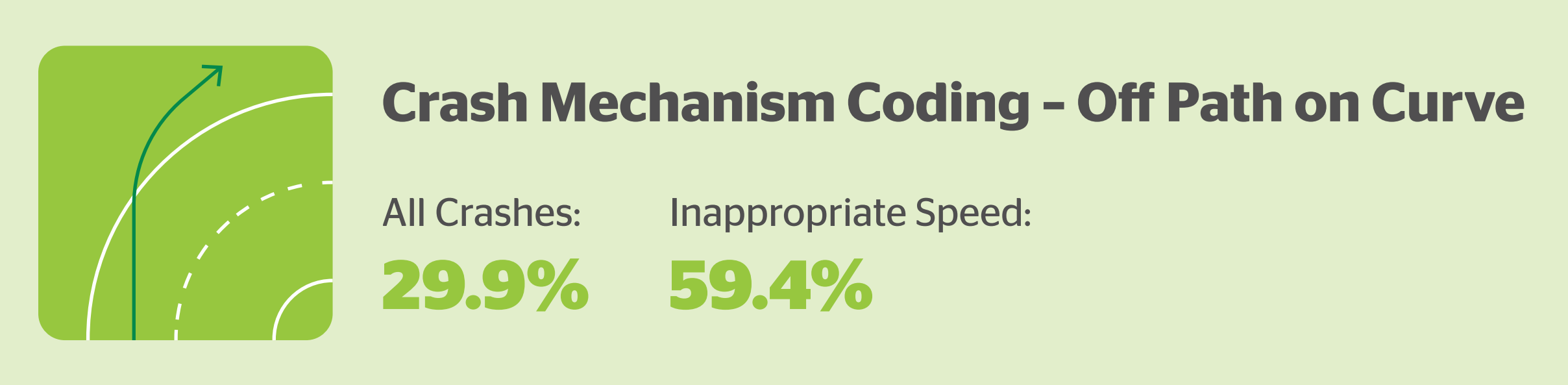

NTARC data shows a vast majority of inappropriate speed-related incidents occur in bends and most often result in vehicle roll-overs. In fact, the latest NTARC data reveals off-path-on-curve crashes are the most common mechanism for incidents resulting from inappropriate speed at 59.4 per cent compared with 29.9 per cent for all other crashes.

These incidents most commonly take the form of single-vehicle ‘un-tripped’ roll-overs, meaning the vehicle rolls due to the combination of centre of gravity and speed initiating the crash event.

In reviewing the circumstances of inappropriate speed-related crashes, he says most incidents either involve drivers who are extremely familiar with the route/task where the accident occurred; or drivers for whom some combination of the route, vehicle or loading is unfamiliar.

Dealing with The Unfamiliar

Gibson notes that when driving a heavy vehicle, a driver relies on their experience and judgement to decide how fast the vehicle can safely be driven along a route or around a particular bend.

Where factors influencing the handling of the vehicle change, this creates a risk that the driver incorrectly assesses the vehicle’s limits.

This is made significantly worse when the driver is unaware that something which affects the handling of the vehicle has changed, such as a change in the centre of gravity of the load, he adds.

To manage this risk, Gibson has three suggestions:

- Drivers should be made aware of any changes to the size and/or structure of the load they’re carrying. “An example of this might be a front-end loader operator who puts a large boulder into a tipper; if he doesn’t let the driver know of the unusual loading, any incident is more his responsibility than the driver’s,” he says.

- Operators should look for opportunities to empower drivers to observe changes in their load which might otherwise be hidden from them. This could involve adding a camera and display so that drivers can see into their tipper bodies when on the weighbridge prior to leaving a quarry. Or it could involve installing a smart onboard mass (OBM) system that records and allows drivers to easily view gross, axle, and tare weights from within the cab.

- Encourage drivers to consciously assess what, if anything, is different about their current load. If they’re pulling a different trailer set than normal or carrying a different cargo, they should be considering how that will impact on the dynamics of the vehicle,” Gibson recommends.

Familiarity Breeds Contempt

Conversely, truck drivers who repeatedly complete the same freight task tend to leave less of a margin of error in how they drive the vehicle, he says.

This results in incidents like having a truck roll-over at the roundabout 900m from the depot, which the driver has driven through literally hundreds of times before.

Gibson says this phenomenon is particularly challenging to manage because you’re combating a fundamental human character trait – that of familiarity breeding contempt.

“To that end, the first strategy to put in place is to highlight the risk that complacency can create and try to start a dialogue with drivers around locations and scenarios where this could impact them,” he advises.

“Another strategy is to look for indicators that drivers may not be driving with a sufficient safety margin. If your vehicles are equipped with Electronic Stability Control (ESC), you are able to see where the system is intervening to keep the vehicle on its wheels and compare how regularly such interventions are occurring.”

Keeping Trucks Shiny Side Up

Looking beyond the driver, Gibson says there are other actions that can reduce inappropriate speed crashes, such as optimising the design of vehicles and combinations to maximise stability.

He points to examples where a combination of improved driver performance and better vehicle design has had had a significant impact on inappropriate speed roll-over crashes.

“Probably the best of which was a program of work undertaken with the forestry harvesting industry around Gippsland in Victoria (where) they achieved a dramatic reduction in rollovers which in turned saved lives and money,” he notes.